<< Issue 33

Anthony Caleshu

REVERIES: TEN WALKS THROUGH PLACELESS LANDSCAPES

(after Shara Hughes and Emma Webster, and the Reveries of Jean-Jacques Rousseau)

1. Chaos in the Air

There’s a sun hidden behind the hills… or the clouds, whichever comes first.

Wherever we look, the brightness belies the emptiness in the trees.

Sometimes the sky has a sun, sometimes the clouds have a sky.

We’re starting the day with a walk, we tell anyone who will listen, but there’s no one to listen.

Who needs sugar? Who needs tea? we ask our neighbours.

We’re feeling so good about our walk, which is going so nowhere, so now.

Of the million stories about walking – through the forest, along the riverbank – none are as estranged as this one.

Like a loose-limbed son lost to low blood-sugar are the branches above us.

Like a millionaire’s daughter backpacking through the rainforest with a machete, we’re cutting through the thickness.

We’re enjoying our tiempo familiar, our famille du jour, we tell everyone we pass, but there’s no one to pass.

Mother-of-pearlescence – spectrum of cotton candy – sticky as a diesel spill out of the sky.

Out of the sound: new vowels in our mouth.

Estuary in: estuary out.

Pink and blue as the shadows we’re cultivating to watch the sun set.

2. Natural History

The children study Mandarin in the morning, Portuguese in the afternoon.

The youngest cuts swede, loud as gunfire, to roast in honey with parsnips and carrots.

There are recipes for marauding which we take from TV.

There are recipes for disaster which we take from our walks.

We wonder what is happening to our office plants?

On our walk, today, the fern’s fronds were pre-fossils – embedded in limestone, Jurassic maybe, or Thoracic?

Is it just me, or do you have a sore back, a sore throat?

The trees we walked through were bare of leaves and haunted.

In our mind’s eye, we saw spirt-bottles stuck to the ends of their skeletons.

Like the surgeon said (on the mountain top, in a cave, scalpel in hand): so green, it’s gangrene.

Our mind stumbles with our feet, until lodged, like abandoned nests in high branches.

A cloud hangs low as fruit in the clearing.

Whipped cream, sweet and fleeting as the children like, is whipped in from the clouds, prompting a series of falls and rapids.

The misfortune of the imagination is that it never cools, we tell each other, over early, mint-muddled cocktails.

3. Attraction Contraption

Because we weren’t looking, the belly of the flower surprised us.

Like a squid, it pulsed and inked its shape.

The unidentified psychological state we were in was due to the unidentified smell of an unidentified substance in the air.

Where were our kids?

The rabid foaming from the mouth of the flower was something to fear, we said.

It spoke of mountains and deserts.

As if sex and death were all around us.

As if the flowers we collected were vibrating like the toys we’d bought for the bedroom.

We harped back to memories of being happy on the moon.

Why were we feeling so sticky and shameful?

As if dosed and sweating from the backs of our necks.

As if this flower were an ear – and out of its ear, a tongue, whispering into our ear.

We were torn between wanting to be outcasts and wanting to be cast in stone: like the flowers that were blooming everywhere (people nowhere).

Sleeping became a stranger to us – in and out of days.

There were no strangers to sleep with, not that we ever slept with strangers.

Raving, like réverie, became another’s vagari.

Little did we know, but each walk was like cutting flowers at the stem, a polite excuse.

4. Nouveau Nocturne

It took the landscape to make us feel ancient.

Or maybe we’re confusing ancientness with anxiety.

The need to hack in our Polo shirts through a links course with a 3 iron.

The trees we passed were like the trees we passed the day before.

Sometimes you have to run through the darkness to get to the sky, we told the kids.

We ran, like water, through our own fingers – a leaky cup.

There was a wildness to the verdant, flailing like a bird against the blue.

Where were the birds?

The sun was a golden dot behind the globular moon.

When the night became authentic and raving – everything became more apparent.

The purple richness of the trees presented itself like a euphemism.

But there was no fog above the trees.

No trees above the fog.

No boars rooting for truffles.

Nobody swimming through the lakes or sinking in the quick-sand.

Because this part of the world was thick with light and water, we felt light with flowers and fauna.

We returned home with a late season’s flower pinned to our sleeve.

Red petals which whispered something about conspiracies and mutual dissent.

5. Sigh

It wasn’t until Winter that we began to take it personally.

To live in our own home required a certain rhetoric.

When even the landscape shudders, what difference does it make if you log-on a little later? we asked ourselves.

Like hidden thorns, on the stem of something not a flower.

Like rolling hills, when the landscape is flat.

Once you take the form of company, you become a matter for inquiry.

If not here, where can we find happiness?

One of us claimed the office for an office.

The other, from the converted loft, could see the sea.

What else to do, but pose like trees in front of the TV?

Like a tree twisting into the shape of another tree.

Like a person wishing they could see another person.

We scheduled drinks with others on Zoom.

Who – we never asked each other – is lonely?

You missed the water-cooler conversation – I missed the Friday night beer I never had.

It was only a matter of time, before we began to contemplate the flight of our Souls.

Until my Soul said to your Soul –

To be tired feels like being tried.

For what?

The sun sighed as if was already summer.

We called out to the children on the X-Box below, Let’s take a walk…

6. World in Flux

Sometimes we take a walk to get the house out of our hands.

Sometimes we take a walk because the word walk and the word world has become tautological.

Like green is tautological of blue.

If not tautological, juxtapositional.

Like blue is a monkey on the back of grey.

The white ferry that used to come ashore now floats just beyond our vision of the horizon.

If only we had a reason for feeling more sens exclue than others felt sens exclue?

When can we return to France? we asked ourselves daily, though we’d never been to France.

What’s the mood – after the holidays, after your birthday, the Solstice, President’s Day?

Whose benediction were we seeking?

Where the wind whips the trees hardest and the sky brightens wisest against the water –

If it’s true that even language gets lost in the landscape, nothing is safe, not even this sound: of wind whipping through the trees.

In another language, the word landscape sounds like a song underwater.

Like sea-grass tickling your belly, the wind makes its way through the trees.

The largest tree in the park struggles to stay rooted under our children, hidden in the leaves.

7. Sun Chills

We picked a bad day to begin the rest of our lives.

The walk on the promenade was meant to show us a new sky.

The new sky reflected an old mood – until it became like a new mood.

To be asked to take a walk was to lose the language of the walk, said the children, who opted to stay home.

It was unintentional: how the clouds made up for lost circumstance.

How we felt: like walking a tight rope above a difficult conversation.

It was uninhibited: the way the weather lost its reason for connection.

If only our thoughts – on the history of thinking, on the ghostliness of walking these streets – were dissimilar to those around us?

Each virtue we had was inadmissible as evidence.

The dining room went from overly-familiar to un-familiar, like the sun to the moon.

With each step, we counted residual steps.

Like the bay’s waves, we felt like a collection of breaking peaks.

We challenged the monologue performed by the sea wall.

In response: wildflowers bloomed on the beach, and each flower braced itself like a sentence.

The thought of a walk, we sympathized, was worse than the walk itself.

8. Mourning Reality

Everyone was saying the same thing: about an early Spring.

About leaving the names of flowers behind with the Winter.

The flowers at night were heavier than our hearts in the day.

To not just behead a flower, but to cut it off from the base of a stem, so it might not bloom again anytime soon.

The flowers had the temperament of thieves.

Until we confused their names.

Begonia? Dahlia? Hydrangea? we called, as if the names of our children.

As if we were losing what we both feared and wanted most.

The flowers we loved most were the ones whose sex grew in the night.

The flowers that might behead us in the night, while lilting, weeping from the inside out.

What can you steal from a flower that has nothing?

Except their scent, and their touch.

Until behind their lazy eye, we had to run from the landscape, back to the house, as if on fire.

Who was on fire?

Out of the chase and into the fire.

Until we became as foreign as fish at the bottom of the ocean.

Unable to walk and talk at the same time.

As if our tongues were pulled out of our mouths.

As if, with a flush of embarrassment, the flowers closed their eyes, so we wouldn’t have to see what they’d already become.

Became.

9. On The Rise

There is a waterfall, we promise the children.

And that somewhere is here, in every step of this walk.

Which, you’re right, sounds like bolognia – a meat-processed substitute for bullshit… left on the promenade by the neighbour’s bulldog.

But this promised waterfall isn’t just bulldog, it falls from the same height as the clouds, on top of the hill, call it a roof garden.

Nothing falls as heavy as water from a roof, heavy as your feet, plodding through the fields of flowers, dotting the landscape.

As if the landscape we’ve walked – past the corner shop, up the steps, down past the park – offers a new path.

Call it physical dissonance – we’re both wet and dry from the rain, standing next to this run-off, due to the absent guttering.

Both tired from and of walking, from and of.

Which prompts us to ask about our emotional capacity to connect during difficult times.

Contradictions of expression rhyme with feeling.

Like the sun, we want to rise into history, into remedy.

Into a new source, by which the water comes and goes.

From where?

To whom?

10. Bliss (Windows)

Eventually, not even the idea of a walk can get us where we want to go.

We say this tenderly, as if in therapy.

The routes we like most no longer take us out of our minds: to the woods, to the water.

We no longer feel like walking on water.

We dive deep down into the sea-grass.

Once: we watched a friend dives deep into the blackness and rise with a bleeding egg from the top of his head.

Another time, an alligator stayed so silent by the bank, a heron walked onto his back, as if into a fable.

After cutting through the overgrowth, the waters were as blue as blueberries, if blueberries were sapphires.

Spot the bather – saved or forgotten – by the dawn left over from the dusk.

The notes we take while walking serve as a reminder – no matter how bored you are, you can always get more bored by taking another walk.

A joke! Like a coming-of-age story (our children); like coming-into-being (light into the trees).

In the distance, clouds gather before they explode.

As if from our hearts.

Whatever your vice, whatever your afternoon, we rehearse memories of our time together.

As if on holiday.

As if in a house with an expansive lanai, set here – no, there – just across the lake.

The sound that surfaces, chittering or cheering, from those watching the Superbowl, or March Madness.

What month is it?

Time is just one of the many things with teeth nibbling at our conscience.

We have so much more to tell you, but we’re beat, and the soles of our feet have turned the colour of putting one word in front of the next.

Like a long and unexpected kiss.

NOTE ON THE POEM

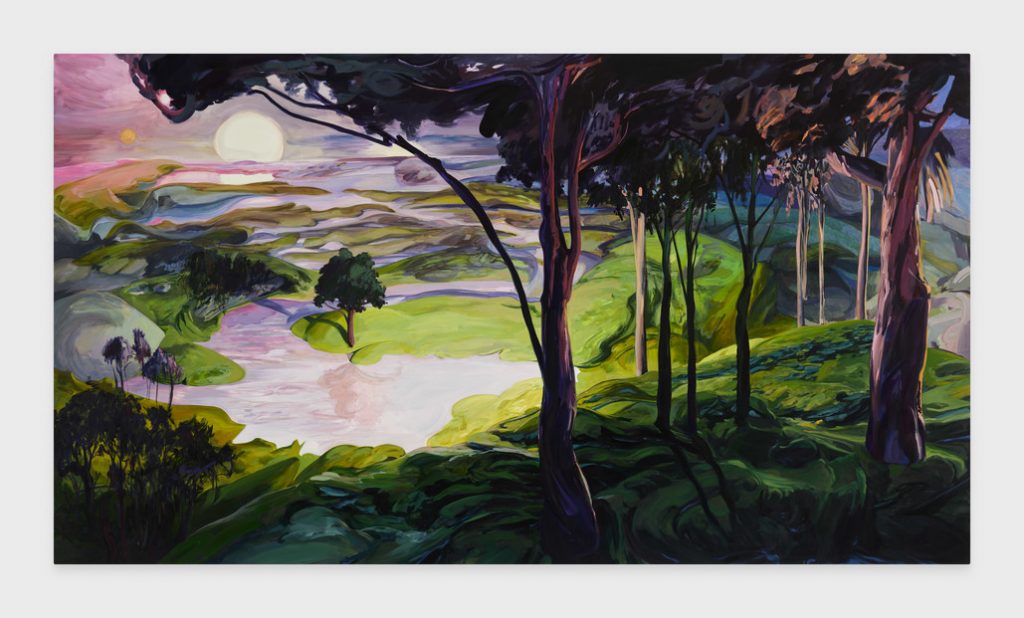

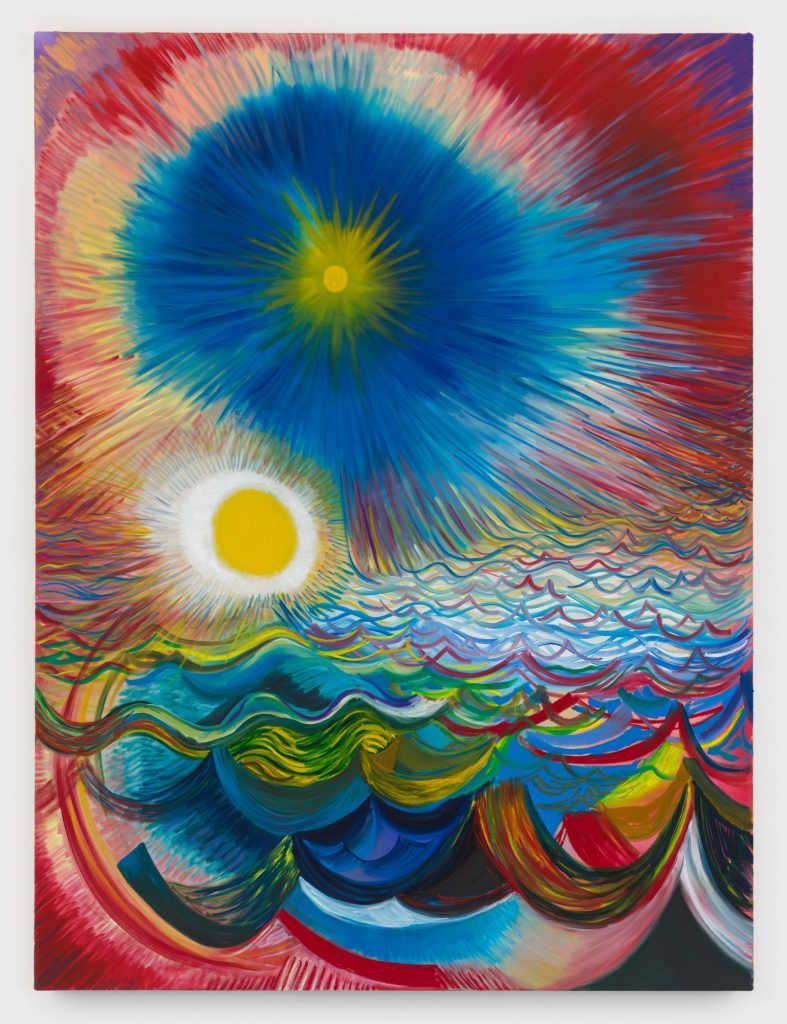

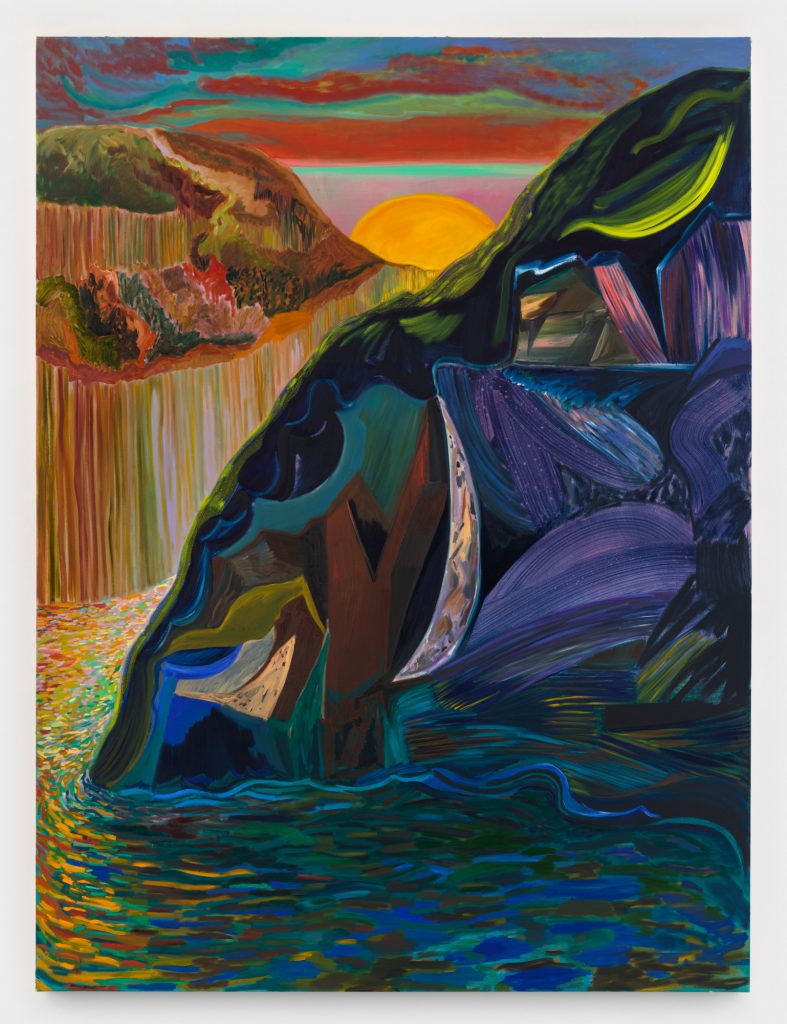

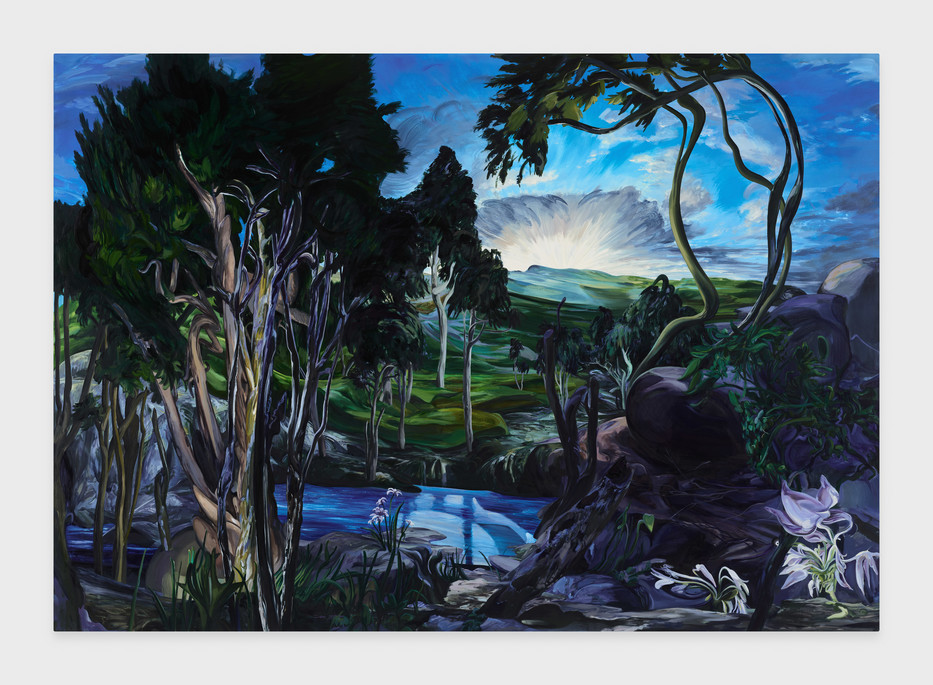

The 10 sections of this poem take and alternate their titles from paintings by Shara Hughes and Emma Webster:

- Shara Hughes, ‘Chaos in the Air’, 2020

- Emma Webster, ‘Natural History,’ 2020

- Shara Hughes, ‘Attraction Contraption’, 2021

- Emma Webster, ‘Nouveau Nocturne’, 2021

- Shara Hughes, ‘Sigh’, 2020

- Emma Webster, ‘World in Flux’, 2021

- Shara Hughes, ‘Sun Chills,’ 2021

- Emma Webster, ‘Mourning Reality’, 2021.

- Shara Hughes, ‘On The Rise’, 2020.

- Emma Webster, ‘Bliss (Windows)’, 2021.

Hughes refers to her ‘imaginary’, ‘placeless’ landscapes (Landscapes), while Webster talks of her landscapes as ‘a world that doesn’t exist… that you can’t visit… [that] have to exist as an expectation instead of tangible reality’ (‘Postcards for places you can’t visit’, ICA Miami, YouTube Channel). Both seem to capture a world before people / before language… or, possibly, after people / after language. ‘Trees and flowers become figures in the paintings’ (Hughes, Landscapes). ‘How wild would our world be if we sort of treated trees as people… we need a sort of larger spectrum of emotional understanding with other beings’ (Webster, Green Iscariot). The natural world dominates, over-grows, over-takes – the genesis of human life is in tension with the end of human life (post-apocalypse). All paintings by Hughes and Webster cited in this poem were painted in the first years of the Covid-19 pandemic.

*

In Jean-Jaques Rousseau’s Reveries of the Solitary Walker (1782), he takes 10 walks, seeking ‘refuge… cut off from all communication with the rest of the world, ignorant of what passed there, that I might forget its existence, and that mine also be forgotten’ (Fifth Walk). Moving between declarations of personal persecution and affliction (from what he takes to be an uncaring and uncivilised society) and, simultaneously, ecstatic pronouncements of joy from his solitary walks in nature, Rousseau can read as manic: ‘Lonely and forsaken, I felt forward frost steal on me; exhausted imagination no longer peopling my solitude’ (Second Walk); ‘Beautiful flowers, enamelled meadows, refreshing shades, brooks, groves, and verdure, come and purify my imagination’ (Seventh Walk).

Although romantic (and inspiring of the Romantics), it is hard to always read Rousseau’s walks as romantic, as in idealizing, as in loving (see Rousseau’s justification for putting his five children in the Foundling’s Hospital in the Ninth Walk). It felt both odd and attractive, to imagine, during the pandemic, what it might have been like to be Rousseau, walking and writing in the 18th Century; and likewise, to imagine what it might be like for Rousseau to be me in 2020-2021 (with wife and children, two teenagers who, in short time, came to hate the daily, enforced walks). Rousseau is one of a long line of writers for whom ‘walking animates and activates my ideas’ (Fourth Walk), professing how ‘my mind moves only when my feet do’ (Ninth Walk). During our walks, I began to think that Rousseau might have been walking when he came up with the ideas expressed in his earlier ‘Essay on the Origin of Languages’ (written in the 1750s but, like his Reveries, also published posthumously). ‘[Rousseau’s] “Essay on the Origin of Languages” is probably the most outrageous thing he ever wrote, and one of the least plausible of the numerous general treatises on language in the history of western thought’ (Newton Garver, ‘Derrida on Rousseau on Writing’, The Journal of Philosophy, Vol 74.11, 1977). Rousseau charts language’s evolution from South to North. He believed an authentic experience might come from an authentic language, which might paradoxically (and idyllically) have begun as either non-vocal and gestural, or entirely metaphorical: ‘the first speech was entirely metaphorical, literal speech coming only later… as a degeneration… grammar and articulation reduce the expressiveness of a language’. If less articulate, less exact, less clear, an expressive language is also less prolix, less dull, less cold, he argued. Why do we need words when we have passions? If the only thing we are missing is articulation and explanation, could we choose to live without articulation, in a state of perpetual mystery and wonder? What of this in the context of walking? Could we walk our way back to an authentic language as a way to better engage the landscape?

The visual artist’s recourse to material paint (without the need for literal language) would seem, by Rousseau’s account, more apt than the writer’s lost (if not impossible) linguistic mode to authentic (and sublime) experience. I imagined our local landscape, void of people, superimposed with the fantastical landscapes of Hughes and Webster. I imagined a conflated version of Rousseau and myself – walking alongside a conflated version of his long-term partner, Thérèse Levasseur, and my own wife – his five children conflated with our two children. I imagined returning to ‘the first speech’, the ‘metaphorical’, through 10 réveries (from the Latin vagari, meaning wandering), until I got to that place of last speech, or lost speech, the world no longer occupied by anyone but us. Walking through the woods, or by the sea, clouds and rain in our headspace, waves breaking under the sun, sky over the horizon, through blue and gold fields. I imagined returning home, in silence, without language (without elaboration, with no embellishment), but with flowers for the dining table: ‘Instead of stupid manuscripts and musty books, I filled my apartment with flowers and plants’ (Rousseau, Fifth Walk). Over time, the line between real flowers and plants, and paintings of flowers and plants becomes as hazy as the horizon. Over time, as Rousseau proved, as much as a walk can generate high emotions, a walk can also result in wayward indictments of society and spirit, a victimisation of the very self and life which is being served and celebrated. What kind of help, I asked Rousseau while reading him, could he offer so that walking with language (into expression, into metaphor) might enable mystery and wonder, to allow for reflection on times of great uncertainty?

*

Shara Hughes’ work can be seen at the websites of galleries, David Kordansky, Pilar Corias, and Eva Presenhuber, as well as in her books: Landscapes (New York: Rachel Uffner and Eva Presenhuber: 2019), and Shara Hughes (Dr. Cantz’sche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co: 2022). The works of Emma Webster can be seen at Webster’s website as well as those of galleries, Alexander Berggruen and Perrotin, and in her book, Green Iscariot (Alexander Berggruen: 2021). A short video of Webster talking about her art can be seen at, ‘Postcards for places you can’t visit: Emma Webster, landscapes and VR’, Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) Miami, YouTube Channel, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vV1XETzOlPo.

Citation of Rousseau are taken from Russell Goulbourne, Reveries of the Solitary Walker (Oxford UP: 2011), and/or The Confessions of J.J. Rousseau, Citizen of Geneva, Part the First, to which are added, The Reveries of a Solitary Walker. Translated from the French. Third Edition. (London: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1796, available as a Project Gutenberg of Australia ebook no. 1900981h.html, most recent update March 2022: https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks19/1900981h.html#ch9.

Anthony Caleshu’s fifth book of poems, Xenia etc, is due out in Spring 2023 from Shearsman. As with the poems in this issue, the book aims to jump from the ekphrastic tradition into the contemporary condition. He is Professor of Poetry at University of Plymouth, where he directs the MA Creative Writing, and publishes the small poetry press, Periplum.