Landscape with planet on table

i.

World landscape

That world, which never existed in the first place, is gone. Forest and desert, mountain and valley, ocean and river, cloud, cave, archipelago and plain, gathered all and dappled, here and there, with intricate cities and fountains, scenes of judgement or war, village or festival or caravel in full-sail, paradise garden or prospect of hell, the occasional myth brought down to earth or sea, the fallen pair, the poisoned girl, the splash and the drowning boy whom no one marks but you and who, anyway, is past all saving.

“World landscapes”—Weltlandschaften—are a genre of sixteenth-century Flemish painting that collect in the space of a single picture-plane all the varieties of landscape the artist could imagine, intermingled with representations of human and animal life, small against the vistas that enfold them, naked, somehow, even when clothed. How absurd, to tamp the world into a grain of sand, pack the solar system in a suitcase, set the planet on the table.

They are a form of fiction. Why look at them now? What is their allure for a time that has succeeded, extravagantly, in mapping the world with ever-greater precision? And why do they so often seem animated by a wind from paradise?

One answer: world landscapes make an imaginative gamble. They show that the world as it is cannot be encountered without the possibility—or the shadow—of the world as it might be. They ironize the idea of “the known world,” a phrase to make any skeptic’s heart beat faster, the idea that to survey a landscape is the equivalent of understanding or possessing it. They picture paradise on earth only to demonstrate that paradise itself is a question of limits. And (this is the joke): from its limits, sometimes called walls, paradise derives its potential and its essential disaster. The rest is elaboration.

The most famous painter of world landscape is Pieter Bruegel—and arguably the most skilled—Landscape with the Fall of Icarus is one notable example. And yet, Bruegel is not without predecessors and contemporaries: Joachim Patinir, who learned much from Hieronymous Bosch, Herri de Met Bles (Patinir’s nephew?), Lucas Gassel, Cornelis Massys, Albrecht Altdorfer, the Brunswick Monogrammist, Peter Paul Rubens, Hercules Seghers. Nor is he without successors. Traces of world landscape haunt subsequent traditions: (the Baroque) Claude Lorrain, Nicolas Poussin, (the Hudson River School), Thomas Cole, Fredric Edwin Church, contemporary photography and plastic arts (Kim Keever, Walter Martin and Paloma Muñoz, Lori Nix). World landscape amounts to a loose category of which Bruegel’s canvasses are a bravura instance.

Weltlandschaft was named Weltlandschaft in the early twentieth-century by German art historians looking back at Dutch artworks several centuries distant and grasping for language to describe. What to call those paintings that drew together, however speciously, “everything that seemed beautiful to the gaze: sea and land, mountain and plain, wood and field, castle and farmhouse”? It is mildly revelatory that “world landscape” owes its name to a period whose trials included World War I, multiple revolutionary failures, and an influenza pandemic.

In long calamity, when reality impresses itself upon the consciousness by its fractures, the spur to make sense of things as a whole is acute. (But when is it not a long calamity? The world hangs in the balance, one way or another.) This spur is always desire for a world that never exists in the first place, though it is not necessarily the desire for total knowledge, authority unbound. A utopian impulse sometimes rests, like one of Donne’s gardens, on the persuasiveness of its flaws: “And that this place may thoroughly be thought / True paradise, I have the serpent brought.” World landscape names the will-to-totality that sometimes animates the fantasy of a Weltanschauung (world view) or else Heidegger’s Weltbild (world picture), which diagnoses modernity as the condition of knowing the world as picture, as a whole whose arrangements always refer back to the attempt to invent, at last, the human. This name also signals a desperate need for a form of knowledge much lower to the ground than omniscience: a working theory. Both impulses are comprehended in Weltlandschaft, a term that says as much about the historical moment of its coiners as it does about a set of paintings in context.

What a name describes is often an act of reinvention as much as the thing itself.

ii.

Landscape with…

They are often titled, sometimes by their makers, sometimes by subsequent curators, under the formula Landscape with…: Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, Landscape with the Flight into Egypt, Landscape with Orpheus and Eurydice, Landscape with Narcissus and Echo, Landscape with the Judgement of Paris. This convention of naming marks a question of scale: world landscapes represent human activity from a great distance, so that, as a rule, individual figures are dwarfed by their vast surroundings.

And yet, “landscape with” titles do not betray the curious tendency of these images to pick out in obsessive detail the tiny human forms that inhabit them. All this concern for the minutiae of these small beings! They are not solely staffage, figures drawn to demonstrate the scale of other pictorial objects. Their insistent particularity is the statement of a problem of the limits of human activity in a world only beginning to know itself at planetary scale, by Magellan, Mercator, and Ortelius, by atlas, telescope, and globe.

Erdapfel (c. 1492 – 1493), Martin Behaim, German National Museum1

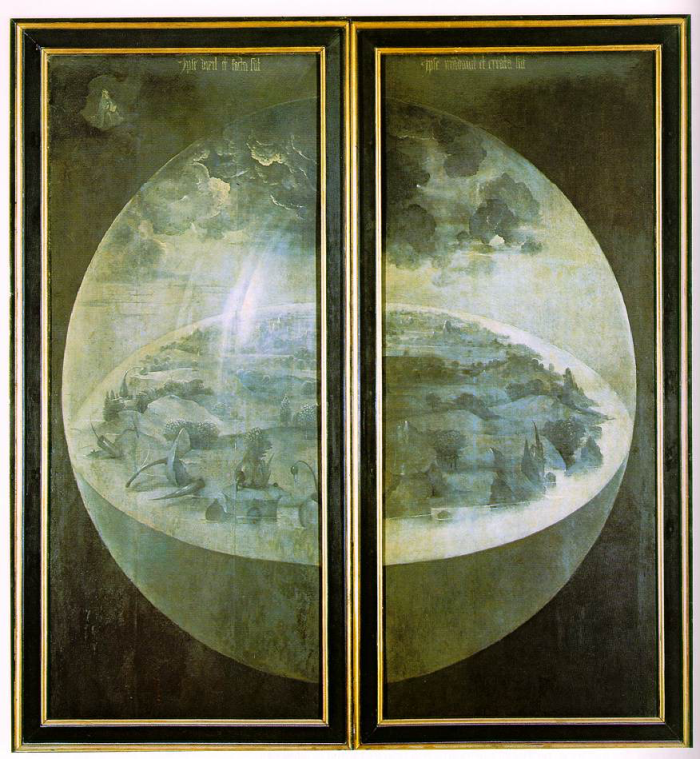

Martin Behaim’s Erdapfel (earth apple; potato), the most ancient terrestrial globe extant, dates from the late fifteenth-century, approximately the same decade when Hieronymous Bosch was painting The Garden of Earthly Delights. The exterior of Bosch’s triptych, less well-known than its interior panels, portrays the Biblical creation of the world on the Third Day, when God set the lights in the firmament, the lesser and the greater and the stars, and called it good. Encased in a vitreous sphere, the scene: nether curve silted with earth and plants that frill and bell, sails almost, animated by wind—cloud-curding vault—as if all globes, peeled of their gores, concealed vivariums, quietly incubating life.

A hazy streak marks the left hemisphere of the sphere’s glassy enclosure, reflection of some light source outside the world? But what (save God, save you) is outside this world? Writing about Velazquez’s Las Meninas (1656), with its sophisticated perspectival experiments, which implicate the observer and the painter in the image, Foucault invoked a “demiurge of knowledge fabricated with its own hands,” meaning humanity, self-fashioned, which had aged so rapidly that it was easy to give in to the illusion that this “quite recent creature” had always existed, always prematurely old, waiting out the millennia in some obscure universal cabinet for “that moment of illumination in which he would finally be known.” Only, as Foucault understood, the illumination of being known is often fitful, unpicks its work, will not confine itself to a moment. And then the lesson’s to be done all over again. In a way, this is a statement of qualified hope, a fantasy of incompletion, that the world may be rearranged, that what no longer suffices may be recuperated, renovated, that the work of it and the delight of it go on. Knowledge changes its mind.

Why that spectral streak? What does it reflect, except that the artwork is a made object? Half a pale rainbow? A sort of suppressed smile? It might be the demiurge’s, that smile, or the painting’s or the painter’s (by one reckoning, a painter is a demiurge) or, in another world that is this one—yours or mine. The sphere and the streak are visible only at the expense of the Garden, a choice there’s no getting out of: one world landscape or another. When the triptych is shuttered like an eye in its lid, it walls up paradise, earth, and hell. And so it is the third day of creation and now—how odd—you are involved—and the forms of its vile and exquisite sequel, the given world, no longer seem inevitable. Will the panels open on an unfamiliar prospect? A childish question. The insolent, white streak, furred in morning blue, hangs upon the whole atmosphere.

iii.

How time begins

Paradise (c. 1541 – c. 1550), Herri met de Bles’s tondo of the Garden of Eden, is like a diagram of an embryo in cross-section: condensation of sky, forest, mountain, glade and meadow, waters and their coasts. All this is cradled in triple membrane of circles that recall the old Ptolemaic spheres. There is the earthly paradise of Eden, sealed in its walls. The tondo features two curious violations: of the laws of perspective and the laws of time.

Large things and small things, things close-up and things far away, exhibit equal weights of detail, so the viewer can see, with fanciful panoptic precision, the crags on distant mountains, the slim arcs of water tumbling from Eden’s central fountain, a gallery of inquisitive beasts, the drama of exile as Adam and Eve are created, tempted, judged and found wanting, driven east of Eden—tripping towards the encircling wall of Paradise with an evicting angel in their wake. The scenes of the Temptation and Fall, arrayed on a serpentine plan, first enter the field of vision in simultaneity. Where should the gaze come to rest?

Is the temptation to imagine your eye could open to the aperture of God’s, to see all ages and places at once? This kind of temptation is not foreign to art, after all, to the suspensions of aesthetic experience in which time can sometimes seem to dilate or break for a cigarette as you become absorbed in the object. Or is the challenge to perceive, in mortal humility, Fallen sequence rather than the illusions of an Unfallen synchrony of divinity, of paradise-time? Like a prohibition against eating the yields of a particular tree of the whole orchard, eternally ripe, the test is both easy and impossible.

Or maybe this olio of times and places is the shadow of the wings of Benjamin’s recording Angel of History, who, borne backwards on a wind from that same paradise, watches the catastrophes amass, his mouth suspended in an agonized “O.” The triple border of met de Bles’s tondo walls off the Garden of Eden, not least from the observer of the image: that garden in which no decay, no death, no linear time—because life was not yet life. Adam and Eve are arrested in the stress of the instant after the Fall but just before they have stumbled over the limit of Eden, beyond which all paradise will have to be the paradise they make for themselves. All places thou. And that is how time begins.

iv.

How terrible to be God

Flemish world landscapes of the sixteenth century often hung in the dwellings of the bourgeois armchair traveler with a taste for complacent godhood, the omnivoyant view from nowhere. Many were painted in the lead-up to the viciousness of Dutch colonization, the world charted and traded, brought home to the metropole to be carved up at table. They have in them their sinister potentials, so with all projects of collection and cartography: panoramas, maps, charts, archives, libraries, botanical gardens, the ruins of amusement parks or world’s fairs, natural history museums, cabinets of curiosities, zoos.

So with many projects of paradise, the utopian form whose method is often the placement of an encircling boundary designed to frame a devastating trial. The logic of paradise is circumscription. There is a reason why Marx compares the myth of the beginnings of the primitive accumulation—as a separation of diligent haves and lie-about have-nots—to the role of original sin in theology. To understand how this is wrong, it would be necessary to admit that having and not-having are nothing to do with an intrinsically moral relation to work and everything to do with the brutal seizure and enclosure of land, the expulsion of its populations, and their exploitation and expropriation as they are conscripted to labor for private capital gain over resources that might otherwise be held in common. The instruments of the primitive accumulation include imperialism, enslavement, predatory extraction, and violence. Its expressions include the colony, the prison, the detention center, the precariat, the company town, and the etiolation of the public good. When Adam delved and Eve span, who then was the gentleman?

Panoramas, maps, charts, archives, libraries, botanical gardens, the ruins of amusement parks or world’s fairs, natural history museums, cabinets of curiosities, zoos, colonies, prisons, detention centers, company towns, the sleepy couple on the pleated bed, lingering over the bitten apple and the bocca baciata, which does not lose its good fortune to experience, but renews itself as the morning moon does, nibbled to the rind in a passing phase.

In the encounter with a world landscape, sympathy or aspiration need not lie with omnivoyant God, who would not need these trifles, who (poor thing) could only regard a painting on the same plane as a stellar nursery or a volcanic eruption or a dying man. (How terrible to be God.) The peregrine eye might linger, instead, with the little souls (naked, somehow, even when clothed), and shocks of animals half-shadowed by a grove of poplar, the arm of the dying girl, the legs of the drowning boy, the ship and the ploughman, who have their own things to get on with, the fronds of the garden bent by unseen winds.

v.

Impossible views of the world

(I myself have never seen a world landscape in person and may not, given current conditions—this life of reproductions with few originals, locked libraries and proprietary digital portals, of journeys around a room. World landscapes are all that is the case: a view I cannot have of a view I cannot have.)

vi.

Anatomy and algebra

World landscapes anticipate the aerial views that were unavailable to their artists: the earth seen from the eye of a high-flying bird, the cockpit of an airplane, a drone or a satellite, the moon. Of Weltlandschaft‘s three major longings—for wonder, for accumulation and domination, for a perspective that would yield a holistic knowledge of the world, uncompromised (or, at least, good enough)—technology satisfies only two.

The scene from an airplane window, the camera of a drone or satellite, of earth regarded from lunar heights—these things might be wonderful. They might provide information, often the kind of information that will be put to the ends of measurement, orientation, the facilitation of movement, reparative work, useful human endeavor, play, even. They might also yield the data that will be put to invasive or violent ends (surveillance, bombings).

But to the last in this trilogy of longing—for a world that could be understood as a world, interpreted as a world, invented (and so reinvented) as a world—technology and its reports make, in themselves, no answer. Split the Lark —,” wrote Emily Dickinson, “and you’ll find the Music —

Bulb after Bulb, in Silver rolled —

Scantilly dealt to the Summer Morning

Saved for your Ear when Lutes be old.

She ironizes: to vivisect the lark would kill its song, which is no more recorded inside it like a cache of gleaming player piano scrolls than the spontaneous utterance of a human voice. “Dissect him how I may, then” Melville’s Ishmael despairs of the whale, “I but go skin deep; I know him not and never will.” Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) tells how Hippocrates came across Democritus in the garden of Abdera, a book on his knees, studying to write of melancholy and madness, writing and pacing and writing and pacing. Around him on the green-rushed earth, lay the carcasses of many several beasts, “newly by him cut up and anatomized,” as Democritus explained to the revolted visitor, with the aim of discovering the seat of melancholy in some organ of the body so that he might find out its cause and its cure. This end, Democritus left “unperfect.”

How could he have done otherwise? Meaning, though it begins in matter, is incongruent with matter. Burton, writing in the guise of Democritus Jr., takes up this anatomy of melancholy—analysis, dissection—in his great miscellany, which becomes a record of pleasures, pains, and prodigies, anecdotes, jokes, forms of melancholy and forms of pharmacy whose effectiveness is always a matter of hearsay. It is also a chronicle of failures. Not least of these is the failure of an accreting mountain of facts amount to a viable knowledge of the world.

Like his predecessor, Democritus Jr. leaves unperfected the impossible tasks of tracing the wellspring of melancholy or immunizing against it. He treats his own case by the busy writing of melancholic things, though graphomania is scarcely reliable, palliative care. (Also, he loves his ailment.) Anatomy flickers into algebra—in the old medical sense, of Arabic derivation (الجبر), which meant the restoration of broken parts—and neither holds sway, as in one of those Kippfiguren that perplex the philosophers and the psychologists: the vase that’s also two faces in profile, the duck that’s also a rabbit, the woman who is young and old at once. The Anatomy of Melancholy ends rather than finishes. It hath no bottom. One of the six editions published during the course of Burton’s life concludes with “vale et fave,” farewell and be kind.

The melancholic looks at a world landscape with the hunger of a person replaying this valediction from someone they may never see again, with the longing of one who knows that the sorrow and the splendor of any project deserving the name of “world” is that it is abandoned and goes on without you. It doesn’t finish. It hath no bottom.

Melville’s Ishmael again: “God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!”

Melancholy has its lining of indolent honey, of plenitude, the perverse revel in that which cannot be exhausted. It sometimes exceeds Freud’s characterization of melancholy as the unknown loss, which is not conscious knowledge of a missing person or thing but that Sehnsucht feeling when you don’t know what you have lost along with the child or the parent, the friend or the lover, the house or the city or the life deferred or the keys and the little wooden comb with the nacre insets. One aspect of melancholy more pronounced in Burton’s than in Freud’s, was that it comprehended hedonism as well as dejection. The Anatomy sums up these ricochets in the alternating refrains of an introductory bit of doggerel:

All my joys to this are folly,

Naught so sweet as melancholy [. . .]

All my griefs to this are jolly,

None so damn’d as melancholy.

What touches the melancholic about world landscapes is their masterful indecision. In their way, Weltlandschaften also tremble between anatomy and algebra, the criticism that invents the world by taking things apart and the one that invents the world by synthesis, shreds and swatches gathered close to create the semblance of an inexhaustible whole. They have in them the analytic protest of critique: it’s not realistic to plunk down a swathe of tropical forest next to the tundra. The effect of this whimsy is the frisson down the spine that says “things are not like this in real life; the parts do not cohere.” They invite the skeptic’s suspicion. World landscapes are not life studies and cannot be.

And yet, in their immersive enchantment, a synthetic impulse, which critique promises to make way for but cannot, in itself, deliver fully: they portray the world as it never is. They imagine, from its impossible, alienated materials, a form of life in which matter can keep its tryst with meaning, or, at least, where anatomy and algebra can escape for a clandestine kiss. Some are fantasies of a perfected world, which is to say a dead world, at the end of history and art, safe and sterile as a snow globe. Some are odes to an imperfected world, bearable only, lively only, because unfinished.

So much unfinished business. Glum Adorno says that any relation to the new is like a child rummaging at the piano for a chord no one’s ever heard before, a futile task, in one sense. There are only so many combinations the keyboard gives—and so, in his reckoning, the new is the craving for the new, which it may be vital to cling to, and never the new itself.

And yet, there are compositions that take up the dare of that child at the piano. Henry Cowell’s “Aeolian Harp” (1923) requires the interpreter to bend over the frame of the piano and pluck, sweep, and preen its strings rather than depressing its keys, an ethereal technique he called string piano. This way of playing transforms the piano from a chordophone of definitive percussive action to one of strummed or picked vibration. Hovering somewhere between the qualities of a pedal harp and a zither, it hath a haunted sound, full of asymptotes, absences, echoes.

For all that, string piano is a minor form of Bloch’s concrete utopia, the new thing actualized (though perhaps not forever) and not merely the longing for it. String piano answers, literally, the charge to discover new affordances in old instruments, if only by setting the hands to the soundboard rather than the keyboard. Beside the next-to-everything of keyboard playing, this obscure, austere technique is next to nothing, which may be one of its advantages. Strategies of concrete utopia, oriented towards the world and its materials, may need to slumber by next-to-everything and awaken next-to-nothing in order to be anything at all. Auden: “And we rebuild our cities, not dream of islands.”

Oddly—anatomy and algebra—world landscapes, though they are nothing like string piano on the face of them, are also lodged between next-to-everything and next-to-nothing. If in them there is some melancholic loss, it is the loss of the conceit that “things had to be like this” (often a cause for bitterness) and the loss of the conviction that “things have to go on like this” (sometimes a loss that makes heavy things light). Of course, things might go on “like this” indefinitely. Benjamin observes that decline is the rule, rescue the extraordinary thing, “verging on the marvelous and incomprehensible,” the stitch in time. (“That things “go on like this” is the catastrophe.”) And—and—one cannot look at a world landscape forever. But in the sweet stress of regard, the melancholic might become, for a hot minute, the paradisian, who builds the world to lose the world, who remembers that the etymology of “contingency” comes from the Latin for those things that touch one another, who looks at a world landscape (though never forever) and (vale et fave), sees its realism in the marking of a limit, is startled into laughter.

How marvelous, that a world that never existed in the first place might be lost.

How marvelous that some worlds are gone without hope of revival.

How marvelous to be told, with ravishing clarity, that so much will never be yours, that so much is drowned or burned or trashed, that so much, nonetheless, remains and gives delight.

How marvelous, that another world is possible, though it may not be possible for you.

Fatalism has a crack.

vii.

The aftermath

Hard to see the crack in fatalism (or it would not be itself). Another world landscape, Joachim Patinir’s Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx (c. 1515 – 1524) is a drama of this problem. Or it’s become one. It was born to be the drama of a different kind of myopia, a warning to those who don’t tend to their spiritual condition while there’s still time. The matter of the painting is the metempsychosis of the soul from life to afterlife and the destination will be either the Christian heaven or the Christian hell, arrayed on either side of the broad, blue river Styx. Charon, ferryman, psychopomp, broad-backed like the river, rows the naked soul to the place it has earned by its earthly conduct. What life, what death was there? The soul keeps its silence.

The painting suggests that the goal will be Hell. Charon, massive, plies his oar, seemingly without effort, his body and the prow of the boat cant towards the shoals of Inferno. Below his Nephilimic form, the little soul looks inscrutably towards the fires. Although the journey is still unfinished, its end is a foregone conclusion.

The time of decision—of moral action or tempering—is past. This is no paysage moralisé (a contested term), in which a landscape represents some kind of moral choice, between Virtue and Pleasure, for example. Although it may be a scene of poetic justice, not in the sense of “virtue rewarded and vice punished,” but in the sense of an artwork operating, mercilessly, by its own internal logic. For Thomas Rymer, an early theorist of poetic justice, poetry discovers crimes the law can never find out but is never content to leave their punishment to God Almighty and another world—no spectator trusts a Poet for a Hell “behind the Scenes.” Patinir’s painting is poetically just in Rymer’s fashion: it refuses a “behind the Scenes.” Even Frau Welt understands that—Frau Welt, the World Woman, an allegory of sensuous pleasure—her voluptuous statue looks over the cathredral at Worms, serene front, back pocked with pus and vermin. She knows you know she knows she’s not fooling anyone, which is how she wins you over: she is not to be believed because she is not to be believed.

In Landscape with Charon there are no open secrets or hiding in plain sight. There is nothing behind the scenes. It is honest above honesty. All vice is internal vice. In met de Bles’s Paradise tondo, the time of moral activity has just begun; in Landscape with Charon, its time is over. And so, although the river is the zone of transition, the painting contemplates an aftermath: the period between the judgement and the moment when the sentence begins to be carried out.

This is world landscape as postcard from a volcano: a survey for the stipulations for making meaning in any given moment, a portrait of a historical condition—and a snapshot of a psychic state that might belong to the little soul in the boat, resolved on hell. What is it like to be in the grips of an intuition that there is nothing left to be done—nothing left but to watch the shores of fire rush up to meet you with the fervor of a lover? Although Paradise is easily visible from the boat’s position at the center of the Styx (very nearly the center of the painting itself), for the hellbound soul the only rule of significance is the verdict of damnation.

Oh, little soul, you do not turn your head! Why do you not turn your head?

viii.

The soul does not turn its head

Little Soul:

…

…

…

…but I have kept my mind in Hell

and do not know my name.

…

…

…

Why did I tear me—?

ix.

Our moods do not believe in each other

Little soul, just past your crisis and with all of eternity still to come. The grammar of this state of mind might simply be: as I am, only Hell is, resignation as a way of knowing and so a way of being. Marlowe’s Mephistopheles: “Why, this is hell, nor am I out of it.” Milton’s Satan: “Which way I flie is Hell; my self am Hell.” But the soul is not yet in Hell, so, refine: as I am, only Hell will be.

The ponderous Styx, blue division, is the great, central vein of the painting, as wide as Heaven or Hell and as significant: it divides but does not obscure. Heaven and Hell are no secret to one another. Not least among the painting’s ironies is that Hell’s equipped with gates and gatekeepers. Heaven needs none. The soul does not turn its head (you do not turn your head). You look to Hell with Heaven in plain sight, a grammar of possibility foreclosed. The only imminence is damnation. And yet…

…the soul does not turn its head. Any suspense about journey’s end lies in that pinhead profile, focalizing the painting’s lower third. Less and less proximate, paradise—on heaven or earth—is no longer possible for a person in the grips of this hellish grammar. And even if the soul could shift a fraction of a fraction in the bow of the boat, if you could charm the painting to life long enough to convince the hell-gazer that paradise lies open, unguarded on the opposite bank, where figures just as small and exquisite, promenade arm-in-arm among the fountains and the pheasants, the foliage that glows so distinctly in its lines of unfallen deciduous that, as in met de Bles’s Paradise, it violates the laws of perspective, as if your vision were divinely enhanced so you could see close-up and far away at once: the orchards and the winged angels and the doe come to lap, in its inhuman innocence, at the waters of the Styx…

…even if you could intervene to the subtle tune of ninety-degrees of torque, forty-five, fifteen, would it not be an insult to that naked creature, crouched under the arc of the rower’s body? Would it not disregard whatever shred of dignity might cling, still, to its essential failure, to the slant of the skull, chosen, that might be the only decision left to it? The exercise of a stubborn fluxion in the casket of the heart where the mechanism of moral will has evaporated, leaving behind it only a dessicated perfume, fragrant, faint, artlessly corrupt, like rotten figs that eat the wasps to fatten into life. Would the little soul not say to you in a toneless voice, somewhere to the side of human sound: the soul does not turn its head? And yet…

…it explains something, the unturned head, this hell-grammar of meaning allowed, meaning foreclosed. It explains why it had to be Weltlandschaft. The breadth of the environments represented in a world landscape—all the painting knows of what a world can be like—show the limits of that world, whatever can be imagined of ocean and city, garden and desert, pressed together like a crowd in a plaza. And the positioning of the figures—usually dwarfed by the landscapes they traverse, unwitting instruments of scale—speaks of how partial and obscure any single human experience of the world must be, how its pleasures and pains (which may be, for anyone, for everyone, a treasury of secret splendors) necessarily involve selection, the exclusion of some conditions of meaning in favor of the grammars that respond to our immediate forms of life, our immediate situation.

If, in each, there is a changing mirabilary of inner seas and prairies, habitations, estuaries, forests, dunes, vast wastes, rubble and ruin, tundra and taiga, urban light and litter, empty cells and bare, dust-rimed cupboards, views of the Milky Way and the Sahara, swamps and observatories, abattoirs and hospitals, Broceliande and the Marianas Trench, tombs and gardens—if, in each, a matchless world landscape—it is also true that it can be hard to know that wisely or well. Even in the perimeters of interiority, it is difficult to be in more than one place at once. If it is possible—it is possible—to be of two minds about something, to feel more than one thing at once, to be at odds with the self, it is still difficult to experience all forms of feeling as equally available in a single mood or moment.

That would be the detachment of divinity, beyond all earthly positioning. Becalmed in the Sargasso Sea, no ascent to the side of the sky in the Himalayas, even if they occupy the lot next door in your psychic geography. Only some conditions of existence can have meaning in any given passage of time, even though the landscapes that could have meaning might still obtain, unnavigable. What it is to be drowned in contingency and to have lost the sense of the contingent. Emerson: “our moods do not believe in each other.” Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx reveals the pathos of the exclusions of meaning in a state of fatalistic extremity—and maybe the wistful fantasy of what it would be like to function above this limit of exclusion—as the viewer of the painting really does—capable of seeing all possibilities of significance at once, though not, perhaps, of knowing them well.

x.

The right place for love

Although the spectator, at least the kind who wants to say to the little soul, “only turn your head,” might be a bit pathetic too, pathetic in the way of dramatic irony, in which the audience knows something the characters don’t, omniscience or omnivoyance without potency: in this case, one knows that Paradise is nearly close enough to touch. One knows the blue distances in the painting’s upper third, where the river cuts to horizon, the painting’s most sustained decree of line.

Charon’s ferry seems to have traveled downriver from that horizon, which means the last, small periwinkle slope, closest to the river on the painting’s left, a drift of dying blue as it disappears into the more solid turquoise of the river, might be one more among Heaven’s infinite hills or else an intimation of the earth the little soul has so lately departed, less and less vivid as the lugubrious current seeps down the picture plane.

The diminutive size and the pale, washed quality of this hill link it to the little soul; it peeps up at nearly the same longitude as the boat and its peak inclines, like the soul’s face, towards Hell, looks at the boat and Charon’s back and the pointed nimbus of the little soul’s head, as if trying to understand the direction of its gaze. This faded memory of the earth, just at the threshold of perception, may be for me the painting’s punctum. It pierces, as a punctum should. The hill seems to say, with Frost: “Earth’s the right place for love: / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.” And if you could urge the soul to turn its head, not towards Paradise, but towards that hill, towards the smudge of earthly blue, which seems, itself, to have been caught looking?

The hill adopts the angle of the soul’s gaze. The angle gives another account of “the soul does not turn its head,” of the easy visibility across the honest river of Hell to Paradise, Paradise to Hell. When the soul reaches shore and presents its papers, is immured in fires, Heaven will still be visible from any point along the coast of Hell—and utterly remote. In this version of the story, the soul does not turn its head because (dramatic irony inverted), it understands something better than its audience. Maybe this is a scene of merciful delay.

When you know Paradise is forbidden you, when you are on your way to its opposite, you defer as long as you can, if only with a quirk of body English, the time when you’ll be definitively wrecked on Hell’s shore, able to see Paradise forever—and know it forever beyond you. You linger in the last moment when your relation to Hell can be like the viewer’s relation to the painting, one of survey or potential compassion or disgust for those who suffer here—or aesthetic experience, though that’s a less high-minded proposition, Kant and the sensus communis aside. That the soul does not turn its head is the gift the painting makes to Charon’s cargo: it allows the bare thing to dawdle in the dregs of the endurable.

Hellbound, it is a touch more tolerable to keep your mind on your destination than on its most exquisite torture: the reminder of the Heaven that can’t be had. This might explain, too, why the Styx and the sky take up so much space: one subject of the painting is the problem of horizontality’s weird incommensurabilities, how it connects disparate locations but does not allow them to collapse, fortifies the long air between point and point.

Distance marks an arrangement. It does not yield. Things just stand there, knowing each other well. The composition of the image holds its landscapes in frame but they—and it—cannot be held, in all their significance, synchronously. And so, the wide, wide river under its long eyebrow of horizon—the figure of that problem of distance, which the little soul will have to confront eternally—looking back over the river, through the river, as if it were telescope, microscope, kaleidoscope, looking at what cannot be had. The soul remembers the goodness of having and how it works by contrast. The next-to-everything is the truly unbearable. So the soul selects the nothing for the sake of the next-to-nothing—a worldly logic, earthly, though it always was. And so Weltlandschaft, all the landscapes of the world, because the soul does not turn its head.

xi.

The Icarfish

Among the orders of the flying fishes was one called the Icarfish, who rose and fell before the lenses of a Japanese camera crew in 2008, cleaving the air above the waters off Kuchino-erabu for a full forty-five seconds, the longest fish-flight ever recorded, rose and fell, surveyed the world from on high, and, unlike hapless Icarus, was never drowned nor out of its winged element but

beat the foam with tail-fin, luftballon

skipped itself like stone of itself

held its breath as we hold ours

long crescent made like globe’s cloud-curded vault

insolent, white streak

scaled in morning blue

that hung upon the whole atmosphere.

xii.

Worldlings

Had the Melancholic been a real, historical person instead of a mere device (staffage, parable, poetry), they would have learned of the flight of the Icarfish by way of a postcard franked from Bloomington, Indiana, washed-out reproduction of Bruegel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (what else?). Written in morning blue ink sans salutation or closure (which the Melancholic would not, in any case, have needed to identify the sender), it would have apologized for long silence, described the doughty fish’s achievements, and wondered whether it changed the complexion of Bruegel’s painting at all if we believed that he believed that drowned Icarus was not drowned but changed to class Actinopterygii, order Beloniformes, family Exocoetidae, to wit, a flying boy—I mean—fish (how he loved Latin).

The sender, whom I will call the Diver, would have gone on to opine that the “splash quite unnoticed” in William Carlos Williams’s “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” is superior to the “splash, the forsaken cry” in W.H. Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts,” the more famous ekphrasis of Bruegel’s painting. He thought it was because Williams had the restraint to omit such obvious excesses as “forsaken cry.” But that was Auden for you, trading on the stentorious utterance—by God, “forsaken!”—when the next-to-nothing of the splash would have spoken more clearly for itself.

The Diver admired, particularly, the frozen reaches in the upper right-hand corner of the canvas’s world landscape, which he would have liked to study in person someday, by which he meant a trip to the arctic and not to the Royal Museums in Brussels. He said he was trying to be less wrong about suffering that wasn’t his own. So probably he was out of work again or in love or his sister was still ailing or he had betrayed himself in some way, though he wasn’t going to say so and, either way or neither, was unlikely to turn his head.

A child of Indiana from the start, he had, at the urging of his father, who was convinced it was some kind of life, buried himself in loans for college and a law degree and followed the latter to a fracking town in North Dakota, almost entirely populated by men, where the law he practiced, indifferently and then incompetently, consisted primarily of wills, property disputes, and the mediation of violent encounters, which were not infrequent. They were hard hours.

For all that it was a town of men, he missed men, less to talk to than to sleep with (though both were best) and women, less to sleep with than to talk to (though both were best) and subtler sunsets, tamed by the jess of a blue hill or a sconce of wood or tucked into a chiaroscuro ravine or a canal between tall walls. The flatlands of Indiana and those of North Dakota were so different in degree as to be different in kind. These nightly pageants of the greater plains—molten gules and godspouts of baleful, jaundiced cloud—depressed him. They were like imprisonment in a Turner seascape, he said. And Turner was a painter whose canvases ought only to be looked at in moments of high, hilarious ecstasy and the Diver was only the feel of not to feel it. Anyway, he had no expectation of rising to life at that pitch and, in the absence of the chance, the dying day seemed always a persecution. He was trying to keep his head above water, a real puzzler, since he was landlocked. A glimpse of the surface, he theorized (the surface of what?), might sustain him for three, five, seven years.

But every night, the melodramatist sun, so quick to its cue, and under its influence he waned and turned to wax; played Dolly Parton and Yank Rachell and Henry Cowell on repeat; read Ashbery or Henry James, the tabloids, the internet; watched old episodes of The Twilight Zone or Daisy Kenyon again; stalked the sun-ridden air until the heavenly body quit hamming it up and ceded the stage to the Milky Way. He mythologized; it was one of his human failings. The Melancholic’s automatic contempt for mythology was one of theirs, though they later came to regret certain consequential insensitivities.

The Diver had been, by the time he came to correspond with the Melancholic, in search of a Paradisian, but in the meantime, the Melancholic would do. They thought, perhaps, that one reason he liked to write them was because he saw in the Melancholic one who understood what it was to betray oneself and maybe he believed they could keep faith with one another for a change. It might be salubrious. (They never met but once and it was not a notable success.) Witty, madcap, profoundly reserved, his finest works made of style such a palpable, humorous substance that it took a second or third reading to realize their achievement was the transformation of some unspecified misery into levity.

“Poor deer,” he wrote, in a letter of particular brio, “thou mak’st a testament / As worldlings do, giving thy sum of more / To that which had too much.” The Melancholic had had to look it up to realize he was quoting melancholy to melancholy. And after that: worldlings, for the world that was the welt and the world that was the Welt, and “Dear Worldling…” “Dear Worldling…” here and there.

They were aware of themselves as standing lieutenant to one another, the Diver and the Melancholic, like the second bananas out of one of the sophisticated comedies of manners from the 1940s he favored in certain moods, who were used to serving as proxies, whose care was still to do it with élan. For a long time they stood there, knowing each other well.

But by then, his father’s fingers were too swollen for the finer work of an electrician and soon he was dying and the Diver’s sister fell ill and so he returned to Indiana with his debt and his fear of the sunset and his longing for the company of people to talk with and sleep with—and said nothing of regret to anyone (I believe he said nothing of regret to anyone; this far, all instruments agree.). And he let his legal credentials lapse and found a job in a warehouse and later as a custodian in a local hospital and quietly arranged things and often defaulted on his loans and lived in the house where his father had died and sometimes wrote letters.

In the postcard with the fall of Icarus (the last one), he indulged in some gentle mockery at the Melancholic’s expense, for they had become now a real city mouse, despite having grown up in a place quite rural. He apologized for writing such a rarified critter from the wilds of the Rust Belt (a world that had never existed in the first place and was now gone), but which had, nonetheless, some unexpected beauties. And the people of the megalopolis, who had killed in themselves the feeling for unexpected beauties, were only to be pitied their insensibility to these. You think your pharynx is bad? Everyone’s pharynx is bad. But the Melancholic’s pharynx was bad.

And yet, did the Melancholic know of the subterranean affinity between Bloomington, IN and New York, NY, which drew them together as close as the wintry mountains and the indifferent sea in Bruegel’s landscape? Did they know that the Empire State Building had been built from 18,630 tons of limestone quarried outside Bloomington? The quarry, 207,000 cubic feet, a deep cup for water, now, made a skyscraper in negative.

He had taken to illicit swims there, the pleasure heightened by the fear of being caught in trespass and the exhilaration of an unfamiliar experience, literalized by his buoyance in the recondite stillness of the quarry: that there were depths that could not be plumbed and that this could be felt as an optimism, that it was good, for once, to be confirmed by the merely physical in the thing he had been learning so badly all his life—it hath no bottom. To see that, really—to be allowed to see it.

Was that how the Icarfish got on? Was life underwater bearable because one longed for the air, air because one longed for the waves again? How unsettling. He must study to be like the Icarfish and stay alert when he swam at night so he might escape (quoting again) “the delicious death of an Ohio honey-hunter,” drowned in his spoils in a hollow tree, “a very precious perishing!”

Anyway, in closing (off for a swim, will send tomorrow) perhaps the Melancholic would go some evening to the top of the Empire State Building and he, at the quarry, would dive down so deep he would touch the bottomless bottom where there would be an enormous pearl, insolent white, haloed in morning blue, which he would gather up and give to the Melancholic when next they met or maybe by the time you get this postcard, it’ll have coalesced spontaneously on your bedside table—you wear glasses and read and must have a bedside table—just next to your copy of Burton—and don’t tell me you’ve got one already, for sure as I know anything, I know you haven’t a pearl to your worldling name (and still doesn’t and left it unanswered and was wrong about suffering and the unfinished world)—here, the sender checked himself—and don’t you dare pity me—imagine Icarus happy—

The Melancholic would have liked to write back in their intimate argot, now a dead language because a private language and there is no private language, Wittgenstein says, and the Melancholic couldn’t teach another how to speak it even if they wanted to (centuries have passed and the bulb and its generations of moly have slipped, unlabeled, out of the old herbarium). The quirks of wordplay, wrenched out of ordinary sense, the plainwater sentence with its hidden current of anger or eros or laughter, the understated expression of pain, the tatters of poetry and popular music no longer came together in a grammar, though it was pretty to think they could, that a lexicon could be compiled for some unknown hands who might, from idle curiosity, attempt a reconstruction so as to be with the living in the vita nuova of a live language (though it was frightening to think of secret idioms in the mouths of strangers, grammar to grimoir). More probably such a primer, even if it could be assembled, would roll off the edge of the table and lie in the undiscovered country with the other dusty answers and the novelty nightlight in the shape of a globe, its continents warped and smoky where the incandescence had proven too earnest for the all that was the case. The Melancholic sometimes got as far as “Dear Worldling”—a mechanical habit, sitting down to write him—then stopped—an antique watch—the case—rusted—shut—

And that’s all I know of the Diver, which is only what the Melancholic told me and they don’t talk much, though sometimes they say a lot of words.

xiii.

The imperfect

So, this is for the diver at the quarry’s edge, in lieu of—in lieu of. This is for the sleeper, waking in the night and fumbling for the planet on the bedside table. This is for when the pearl is out of reach or pearl there is none. This is for the worldling.

Some ragged wicks of Stevens:

It was not important that they survive.

What mattered was that they should bear

Some lineament or character,

Some affluence, if only half-perceived,

In the poverty of their words,

Of the planet of which they were part.

In “The Planet on the Table,” written towards the end of his life, the poet reflected on his collected poems, which, despite their just reputation for abstraction and difficulty, he hoped would declare themselves, in all their impoverished materials, stamped with the print of the world in which they were involved. In its navigation of a claim on the world that looks like a retreat from the world, this late poem calls across the years to an earlier work from 1942, “The Poems of Our Climate,” which finds someone troubled in mind, arrested, yearning, before a still and silent scene:

Clear water in a brilliant bowl

Pink and white carnations. The light

In the room more like a snowy air,

Reflecting snow.

What it would be—to inhabit that simplified world of carnations and cold porcelain instead of these fractal complications, the planet boiling in its own oil, the whale eaten by its own light, the poems of our climate. And yet, the troubled mind recoils from its desire for that world of “white and snowy scents.” It knows it can’t stay. Poetic justice flexes its talons and nothing for it but to make something of the world in which you cannot go behind the scenes. And so:

The imperfect is our paradise.

Note that, in this bitterness, delight,

Since the imperfect is so hot in us,

Lies in flawed words and stubborn sounds.

In “The Poems of our Climate,” the only viable method of going on is to make do with the materials of the given world and the wrong life—the given, generous but cruel, the life, in which all making is saturated in the wrongness, in which, nonetheless (so hot in us), the imperfect gives on paradise like the wintry mountains on the indifferent sea in the painting that you know. And something—flawed words, stubborn sounds—some signal in the awkward composition gets through, though it will always be for someone else to be less wrong about what, to build a little more rightly, the dividing line and the happy unconcluded, which must be bitter to delight.

That world, which never existed in the first place, is gone. (And yet, it makes life in this world tenable.) Forest and desert, mountain and valley, ocean and river, cloud, cave, archipelago and plain, gathered all and dappled, here and there, with intricate cities and fountains, scenes of judgement or war, village or festival or caravel in full-sail, paradise garden or prospect of hell, the occasional myth brought down to earth or sea, the fallen pair, the poisoned girl, the splash and the drowning boy whom no one marks but you and who, anyway, is past all saving. Some things are better lost.

Can you look at a landscape without describing it? Can you look at a landscape that cannot be described? Can you look at a world landscape at all? Tonight, perhaps. But ask again tomorrow, tomorrow—

This world survives itself, dear Indescribable, dear Erdapfel, dear Eve, dear Adam, dear Poetic Justice, dear Rymer, dear Wrong Life, dear Working Theory, dear Frau Welt, dear Weltlandschaft, dear Worldling, dear Weltschmerz, dear Melancholic, dear Icarfish, dear Icarus, dear Diver, dear Charon, dear Next-to-Nothing, dear Next-to-Everything, dear Landscape With…, dear Frail Craft, dear Present Imperfect, dear Wind from Paradise, dear Angel of History, dear Paradisian, dear Vale et Fave, dear Insolent, White Streak, Maned in Morning Blue. Ah, but what world? Ah, but the planet is on the table! Ah, but the soul does not turn its head!

[1] https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/oldest-globe-erdapfel-behaim

[2] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hieronymus_Bosch_-_The_Garden_of_Earthly_Delights_-_The_exterior_(shutters).jpg

[3]https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/search/objects?q=de+bles+paradise&p=1&ps=12&st=Objects&ii=0#/SK-A-780,0

[4]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Landscape_with_Charon_Crossing_the_Styx#/media/File:Crossing_the_River_Styx.jpg

Rebecca Ariel Porte is a member of the Core Faculty at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. She is at work on a book about Paradise, Arcadia and the Golden Age